El jueves pasado estuve en una conferencia de Daniel Libeskind en Ginebra, justo unos días después de haber terminado el libro Architecture’s Evil Empire? The Triumph and Tragedy of Global Modernism de Miles Glendinning, que denuncia la obsesión de la arquitectura contemporánea por los arquitectos como celebridades y de los edificios icónicos totalmente desconectados de su contexto.

Según Glendinning, la arquitectura de nuestra época es un imperio trágico, que a pesar de tener buenas intenciones – las de mejorar nuestro entorno – hace mucho daño, llenando las ciudades de objetos extraños que no tienen relación con la historia ni con la arquitectura local y haciendo que los arquitectos olviden su misión social por querer ser parte del juego de la fama. La arquitectura del Imperio englobaría todos esos edificios escultóricos que han proliferado en especial después del Guggenheim de Bilbao, que terminan costando mucho dinero, que da lo mismo en que ciudad estén implantados y que los hacen los mismos arquitectos una y otra vez. Mucho ha cambiado en los últimos años, en gran parte a causa de las crisis económicas y de que la gente ha empezado a tomar conciencia que los arquitectos deben hacer más por responder a las necesidades de las poblaciones desfavorecidas y del medio ambiente en peligro. Pero el Imperio todavía sigue siendo vigente, y Glendinning explica que si no cambiamos ese sistema ahora, el riesgo es que cuando la crisis haya pasado, la arquitectura vuelva a la falta de valores que la ha caracterizado en los últimos 35 años.

Last Thursday, I was on a lecture by Daniel Libeskind in Geneva, just days after I finished reading Architecture’s Evil Empire? The Triumph and Tragedy of Global Modernism by Miles Glendinning, which denounces contemporary architecture’s obsession with architects as celebrities and iconic buildings totally unrelated to their environment.

According to Glendinning, architecture in our time is a tragic empire, which in spite of having good intentions – improving our environment – it does a lot of harm, filling cities with strange objects with no relation with local history or architecture and making architects forget their social mission to be part of the fame game. The Empire’s architecture encompasses all of those sculptural buildings that have proliferated especially after the Guggenheim in Bilbao, which end up costing a lot of money, which it does not matter where they are located and which are signed by the same architects over and over again. A lot has changed in the last years, in part because of economic crisis and of people realizing that architects should do more to answer to the needs of people in need and for our endangered environment. But the Empire is still relevant, and Glendinning explains that if we don’t change the system now we are at risk of going back to the lack of values architects have had in the last 35 years, once the crisis is over.

Así que fui a la conferencia de Libeskind con mucha prudencia, sin querer dejarme atrapar fácilmente en las redes de su carisma. Y hay que decir que es carismático. El tipo habló una hora de sus proyectos que tenían relación con la ambigüedad, el tema anual de la asociación que lo invitó a presentarse. Escogió el Museo Judío de Berlín, el Museo Militar de Dresde, una torre de apartamentos en Varsovia, otra en Milán, una casa individual y el memorial del 11 de septiembre. Me gustó mucho su casa individual totalmente extravagante, especialmente porque si hay un proyecto que puede permitirse ser escultórico y no rendirle cuentas a nadie es una casa privada. El museo en Dresde es un edificio del siglo XVIII atravesado por un volumen à la Libeskind que me dio mucha curiosidad por ir a visitar en cuanto tenga la oportunidad. Las torres me parecieron menos interesantes porque eran rascacielos de vidrio estándares y tendría que visitar o leer más sobre el memorial del 11 de septiembre para formarme una mejor opinión. El arquitecto es elocuente, sonriente y simpático. No es famoso por nada.

El único de sus proyectos que he visitado ha sido el Museo Judío en Berlín, que fui en marzo de este año. Este fue el primer edificio que Libeskind construyó, a pesar de ser conocido en el medio gracias a sus exposiciones, entre ellas como uno de los participantes de “Deconstructivist Architecture” del MoMA en 1988.

El concepto del edificio se llama “Between the lines”. El edificio tiene la forma de un zigzag atravesado por una línea recta. El sótano tiene tres recorridos: el Eje del Exilio, el Eje del Holocausto y el Eje de la Continuidad. El Eje del Exilio explica en qué partes del mundo se refugiaron los judíos durante y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el Eje del Holocausto muestra objetos personales de personas que murieron durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. El jardín exterior se llama el Jardín del Exilio y está compuesto por 49 torres inclinadas cuadradas rellenas de tierra de las que crecen olivos en la parte superior. Otra parte es el Vacío de la Memoria, que tiene el suelo totalmente cubierto de placas metálicas con la forma de rostros humanos. Las ventanas del edificio son como cortes y el edificio tiene muchos espacios oscuros, otros oscuros pero con un solo rayo de luz y otros a los que no se puede acceder. El sótano está dirigido entonces a la parte emocional del visitante, mientras que el nivel superior a su parte intelectual. En el nivel superior hay una exposición sobre la historia de los judíos en Alemania, pero que en comparación al sótano resulta mucho menos impactante.

¿Merece el edificio todo el renombre que tiene? En mi opinión sí. Uno puede leer y ver películas sobre el Holocausto, pero recorrer el edificio pensando en el Holocausto te hace sentir cosas de una forma diferente, y el edificio logra su objetivo, al punto que eclipsa la exposición.

¿Merece Daniel Libeskind su reputación? Glendinning cuenta en su libro como en 2010 Libeskind aceptó hacer la fachada para un edificio de Hyundai en Corea. El edificio había sido diseñado por otro arquitecto y estaba muy avanzado en la construcción, pero Hyundai no estaba satisfecho del resultado y buscaron a Libeskind para que lo retocara. Al principio se negó, porque como arquitecto miraba como algo indigno sólo hacer una fachada. Pero terminó aceptando el proyecto, dando un argumento más a Glendinning para denunciar la falta de valores de los “Starchitects”.

Creo que la obsesión por las celebridades en arquitectura refleja la fijación que tenemos por ellas en todos los otros ámbitos: la música, la política, el cine, la literatura, etc. La fama se ha vuelto el sello de calidad de nuestra época: es algo superficial, prefabricado y elitista, pero es la forma en la que aprehendemos el mundo en nuestro tiempo. Hay que estar conscientes de este fenómeno y aprender de él, pero también hay que hacer todo lo posible para no quedarnos estancados en esta visión y pasar lo más pronto posible a otra cosa.

So I went to Libeskind’s lecture with a lot of caution, not wanting to get easily trapped in the nets of his charisma. And he is indeed charismatic. The guy spoke about an hour of his projects that had any relation to ambiguity, the yearly theme of the association that had invited him. He chose the Jewish Museum in Berlin, the Military Museum in Dresden, an apartment tower in Warsaw, another in Milan, a private client’s house and the September 11 memorial. I really liked the single house, totally extravagant, especially because if there is one project that can afford being sculptural and not answering to anyone is a private house. The museum in Dresden is an 18th century building intersected by a volume à la Libeskind and I am very curious to visit it as soon as I have the chance. I found the towers the least interesting of all his projects; they were standard glass skyscrapers. And I should visit or read more on the September 11 memorial to have a better opinion. The architect is eloquent, he smiles a lot and he seems very nice. He is not famous for nothing.

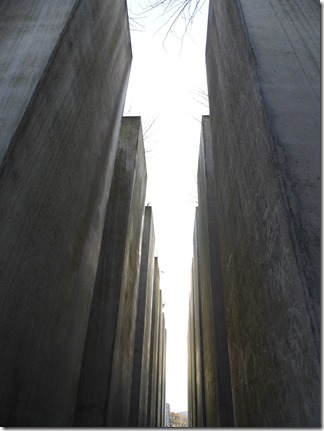

The only one of his projects that I have visited was the Jewish Museum in Berlin, in March this year. It was Libeskind’s first built project, even though he was known thanks to his exhibitions, among them as one of the participants in “Deconstructivist Architecture” in the MoMA in 1988.

The concept of the building is called “Between the Lines”. The building is shaped like a zigzag and it is intersected by a straight line. The lower level has three paths: the Axis of Exile, the Axis of the Holocaust and the Axis of Continuity. The Axis of Exile explains where in the world went the Jewish refugees during and after World War II. The Axis of the Holocaust shows personal objects of people who died during World War II. The garden is called the Garden of Exile and it is made of 49 leaning towers filled with earth and with olives growing on top. Another part is the Memory Void, with its floor entirely covered with metallic plaques shaped like human faces. The building’s windows are shaped like streaks and the building has many dark spaces, others dark but with a ray of light, and others which you cannot access. The lower level speaks to the emotional side of the visitor, whereas the upper level to his intellectual side. There you find an exhibition on the history of Jews in Germany, but it is less shocking in contrast to the lower level.

Does the building deserve its renown? In my opinion, it does. You can read and watch films on the Holocaust, but visiting the building thinking of it makes you feel things in a different way. The building succeeds in its objective, to the point where it eclipses the exhibition.

Does Daniel Libeskind deserves its reputation? Glendinning tells in his book how in 2010 Libeskind agreed to build a façade for a building for Hyundai in Corea. The building had been designed by another architect and its construction was underway, but Hyundai was dissatisfied with the result and reached to Libeskind to tweak it. At first he refused, because he felt it was beneath of him as an architect to do a façade, but then he agreed, giving Glendinning another argument to denounce the lack of value of “Starchitects”.

I think the obsession with celebrities in architecture reflects our fixation for them in every other field: music, politics, cinema, literature, etc. Fame has become a seal of quality in our time: it is superficial, prefabricated and elitist, but it is the way we apprehend the world nowadays. We must be aware of this phenomenon and learn from it, but we must also do everything we can not to stay stuck in it and move onto something else as soon as possible.

|   |

|  |

|  |

|  |

There are so many museums to see - I had never even heard of this one, but would love to visit after seeing your photos

ReplyDeleteI'm so glad you liked the pictures! I'm sure you'll love the building whenever you get the chance to visit it :)

Delete